Johns Hopkins Voice Center at GBMC

6569 N. Charles St.

Pavilion West, Suite 402

Towson

, MD 21204

Berman Parking Garage

Our Services

Comprised of an expert team of nationally recognized, fellowship-trained laryngologists and credentialed speech pathologists, the Johns Hopkins Voice Center specializes in the care of the professional voice. Using state-of-the-art diagnostic and treatment technology, including laryngeal stroboscopy and acoustic and aerodynamic assessments, we focus on designing optimal medical and therapeutic interventions to address the unique needs of performing artists.

Our unique facility offers a fully equipped music studio with Fender® acoustic and electric guitars, a baby grand piano, amplifiers, microphones, and recording capabilities to meet the needs of performers. The movement education studio is designed for body-centered therapy to enhance body awareness and promote the physical freedom necessary for vocal flexibility. VIEW BROCHURE

VOICE EDUCATION & TREATMENT

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

Anatomy and Physiology

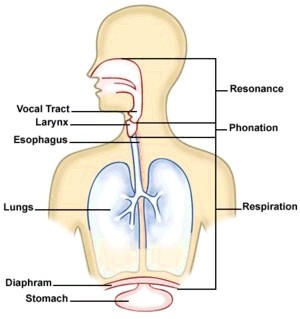

Voice production is a complex action, and involves practically all systems of the body. Voice production begins with respiration (breathing). Air is inhaled as the diaphragm (the large, horizontal muscle below the lungs) lowers. The volume of the lungs expands and air rushes in to fill this space. We exhale as the muscles of the rib cage lower and the diaphragm raises, essentially squeezing the air out.

In order to produce sound, adductor muscles (the "vocal cord closers") are activated, providing resistance to exhaled air from the lungs. Air then bursts through the closed vocal cords. As the air rushes through the vocal cords, the pressure between the cords drops, sucking them back together. This is known as the "Bernoulli Effect." This vibration, or the action of the vocal cords being blown apart and then "sucked" back together, is repeated hundreds or even thousands of times per second, producing what we hear as voice. This sound, created at the level of the vocal cords, is then shaped by muscular changes in the pharynx (throat) and oral cavity (including the lips, tongue, palate, and jaw) to create speech.

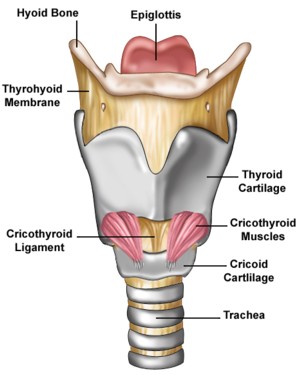

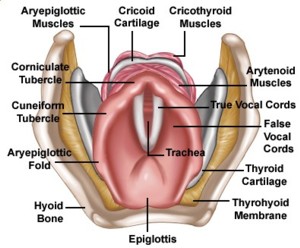

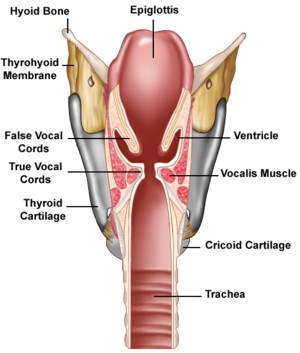

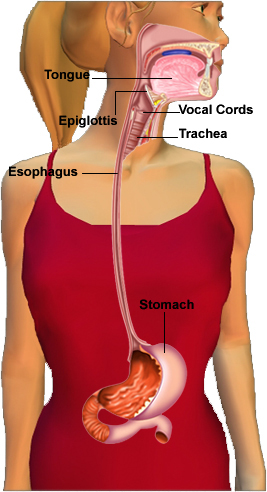

The larynx (lar-inks), commonly called the "voice box," is a tube shaped structure comprised of a complex system of muscle, cartilage, and connective tissue. The larynx is suspended from the hyoid bone, which is significant in that it is the only bone in the body that does not articulate with any other bone. The framework of the larynx is composed of three unpaired and three paired cartilages. The thyroid cartilage is the largest of the unpaired cartilages, and resembles a shield in shape. The most anterior portion of this cartilage is very prominent in some men, and is commonly referred to as an "Adam's apple." The second unpaired cartilage is the cricoid cartilage, whose shape is often described as a "signet ring." The third unpaired cartilage is the epiglottis, which is shaped like a leaf. The attachment of the epiglottis allows it to invert, an action which helps to direct food and liquid into the esophagus and to protect the vocal cords and airway during swallowing.

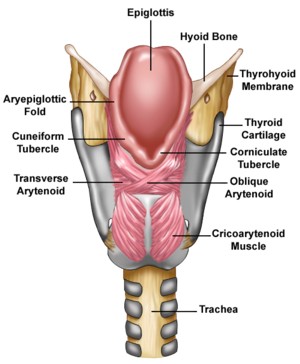

The three paired cartilages include the arytenoid, cuneiform, and corniculate cartilages. The arytenoids are shaped like pyramids, and because they are a point of attachment for the vocal cords, allow the opening and closing movement of the vocal cords necessary for respiration and voice. The cuneiform and corniculate cartilages are very small, and have no clear-cut function.

There are two primary groups of laryngeal muscles, extrinsic and instrinsic. The extrinsic muscles are described as such because they attach to a site within the larynx and to a site outside of the larynx (such as the hyoid bone, jaw, etc.). There are eight extrinsic laryngeal muscles, and they are further divided into the suprahyoid group (above the hyoid bone) and the infrahyoid group (below the hyoid bone). The suprahyoid group includes the stylohyoid, mylohyoid, geniohyoid, and digastric muscles. The suprahyoid extrinsic laryngeal muscles work together to raise the larynx. The infrahyoid group includes the sternothyroid, sternohyoid, thyrohyoid, and omohyoid muscles. The infrahyoid extrinsic laryngeal muscles work together to lower the hyoid bone and larynx.

The intrinsic laryngeal muscles are described as such because both of their attachments are within the larynx. The intrinsic muscles include the interarytenoid, lateral cricoarytenoid, posterior cricoarytenoid, cricothyroid, and thyroarytenoid (true vocal cord) muscles. All of the intrinsic muscles are paired (that is, there is a right and left muscle) with the exception of the transverse interarytenoid. All of the intrinsic laryngeal muscles work together to adduct (close) the vocal cords with the exception of the posterior cricoarytenoid, which is the only muscle that abducts (opens) the vocal cords.

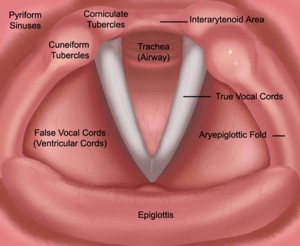

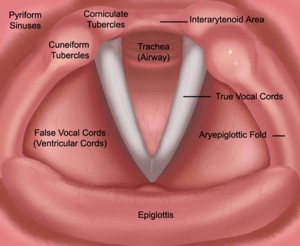

The larynx houses the vocal cords, two elastic bands of tissue (right and left) that form the entryway into the trachea (airway). Above and to the sides of the true vocal cords are the false vocal cords, or ventricular cords. The false vocal cords do not usually vibrate during voicing, but are often seen coming together (adducting) in individuals with muscle tension dysphonia, a common voice disorder characterized by excessive muscular tension with voice production. The true vocal cords open (abduct) when we are breathing and close (adduct) during voicing, coughing, and swallowing.

Caring of Your Voice

Your voice reflects many different aspects of your personality. It's what makes you unique. Lifestyle choices and differences in daily vocal use or misuse can affect the health and stability of your vocal cords. We do know that the effects of smoking and drinking alcohol can have detrimental effects on the voice and may lead to cancer of the larynx. Keeping a healthy voice throughout your lifetime.

Care of Your Voice as You Age - Watch Video

- Don't smoke! Don't smoke! Don't smoke! Also, stay away from smoke-filled environments.

- Hydration matters. Drink at least 8, 8-ounce glasses of water per day (64 ounces); more if you drink caffeine, alcohol, or if you're exercising. Hydration appears to affect voice in at least two ways. First, well-hydrated vocal cords vibrate with less "push" from the lungs. Second, well-hydrated cords resist injury from voice use more than dry cords, and recover better from existing injury than dry vocal cords. Increased systemic hydration also has the benefit of thinning thick secretions (Titze, 1988; Verdolini-Marston, Druker, & Titze, 1990; Verdolini, Titze, & Fennell, 1994; Verdolini et al., 2002; Titze, 1981; Verdolini-Marston, Sandage, and Titze, 1994).

- Eliminate excessive throat clearing. Chronic throat clearing can result in irritation and swelling of the vocal cords. Try sipping water, humming, or using a "baby" throat clear.

- Limit alcohol intake. Alcohol irritates laryngeal epithelium and mucosa, and has been linked to laryngeal cancer risk.

- Avoid vocally abusive behaviors.

- Decrease overall volume; if you're talking one-on-one in a small room, talk quietly!

- No shouting/yelling; find another way to let people know that it's dinner time or that they have a phone call!

- Watch excessive phone talking; you may not realize how loud you're talking while on the phone. Ask your listener!

- Don't whisper! It may actually make your voice worse!

- Don't talk in the presence of a lot of background noise! Talk to someone only when they are an arm's length away.

- Don't try to talk or sing when you have a bad cold or laryngitis.

- Avoid chronic use of mouthwash. Most mouthwashes have a high alcohol content, which can be irritating to the larynx. If you wish, use mouthwash to rinse your mouth... if you must gargle, switch to a mouthwash without alcohol or use warm salt water.

- Posture matters. Good posture allows better airflow and reduces tension and strain. Poor posture can be improved with an exercise program designed to strengthen and realign the body for optimal support.

- Exercise regularly to keep your body, mind, and spirit healthy. Try yoga for the extra benefit of stretch, relaxation, and strengthening, as well as good posture.

- Get sufficient sleep daily .Early to bed, early to rise makes your voice healthy and wise.

- Always warm up your voice before or cool down after prolonged speaking or singing. Try quiet lip or tongue trills up and down your range, or softly and quietly hum five-note descending scales in the middle of your range.

Vocal Warm-Ups

Many singers engage in some form of daily routine or warm-up prior to singing; however, many singers do not know the rationale behind choosing various warm-ups or their actual function. Unfortunately, these questions also elude researchers. A study by Elliott, Sundberg, & Gramming (1995) attempted to determine if vocal warm-ups prior to singing yielded the same effect as warming up other parts of the body, i.e., increasing blood flow to muscles thereby decreasing their thickness and increasing their pliability. Although the results of this study were inconclusive as to the exact effect of vocal warm-ups, several reasons still support the use of vocal warm-ups. Elliott, Sundberg, & Gramming emphasized that changing pitch undoubtedly stretches the muscles. They also noted that many singers subjectively indicated improved vocal functioning following warm-ups.

Warm-ups should not be confused with vocalises. Warm-ups, as in weight training, are used to stretch the muscles to prepare them for work without injury. Vocalises are tasks aimed at acquiring a particular skill, i.e., the actual exercise itself. For example, some schools of thought encourage simple, quiet glides across the range as an effective warm-up. On the other hand, using a staccato (short) "ha-ha-ha" on 1-3-5 of a scale is to encourage onset and flexibility. Many singers will use a variety of vowels, consonants, or arpeggios to "warm" the voice; however, these techniques may actually be encouraging articulatory precision or vowel balancing as in rapid "me-may-mah-mo-mu," or balancing "registers" as in sung single vowels on 1-5-6-5-1, etc.

Vocal Cool-Downs

Although unfortunately and frequently ignored, vocal cool-downs may also be used to prevent damage to the vocal cords. During speaking and singing, blood flow to the larynx is increased. Stopping immediately after prolonged speaking or singing may contribute to a pooling of blood in the larynx, weighing the vocal cords down. Damage may result as one attempts to speak on these potentially swollen folds. An analogy can be drawn to other physical exercise. After running for prolonged periods of time, an athlete is encouraged to walk for several minutes to maintain blood flow and prevent cramping. The same propensity for "cramping" may apply to laryngeal activity. The simple practice of gentle, relaxed humming can serve as an excellent form of cooling-down.

Vocal Function Exercises

Once "warmed," the singer may proceed to daily exercises. The work of Sabol, Lee, & Stemple (1995) explains that many of the exercises prescribed for vocal flexibility are actually calisthenic exercises. Other exercises focus on training the perception of various resonances. A teacher may also recommend the use of isometric exercise, that focuses on improving vocal functioning at the level of the vocal cords. Vocal Function Exercises, first described by Barnes and modified by Dr. Joseph Stemple, are "a series of direct, systematic voice manipulations (exercises), similar in theory to physical therapy for the vocal folds, designed to strengthen and balance the laryngeal musculature, and to improve the efficiency of the relationship among airflow, vocal fold vibration, and supraglottic treatment of phonation."

Optimally, one should hear an example of Dr. Stemple's Vocal Function Exercises to ensure accuracy and efficiency. Most speech-language pathologists are familiar with the exercises, but a compact disc featuring examples of the Vocal Function Exercises is at Plural Publishing.

The Vocal Function Exercises should be done twice in a row, two times per day. They should be produced as softly as is possible with an easy onset (initiation of sound) and forward placement of the tone (avoid a swallowed or dark vocal sound).

Sustain the vowel sound "eee" for as long as possible on the musical note F above middle C for women, below middle C for men. The tone should be produced as softly as possible, but without breathiness. A good supported breath should proceed voice. The "eee" should be produced with an extreme "forward" tone focus; almost, but not quite nasal. The goal is to sustain the sound without breaks for as long as possible. Sustain an "eee" as long as possible.

Glide from your lowest to your highest note on the word "knoll" or on a lip or tongue trill. Voice should be soft, and a forward focus used. If breaks occur, continue to glide without hesitating.

Glide from a comfortable high note to your lowest note on the word "knoll" or on a lip or tongue trill. Voice should be soft, and a forward focus used. If breaks occur, continue to glide without hesitating.

Sustain the musical notes C-D-E-F-G, each as long as possible on the word "ol" ("old" without the "d"). Lips should be rounded; a sympathetic vibration should be felt on the lips.

Vocal Self-Screening

What is your risk of developing or having a voice disorder?

There are certain clinical indicators of problems with the vocal cords, such as actual lesions or the simpler problem of day-to-day swelling. Singers and professional voice users may regularly perform the following daily screening routines to determine if there is a potential lesion on the vocal cords that warrants examination by a physician or if there is a swelling of the vocal cords that would prohibit singing or performing for that day. A good way to use these procedures is to initially screen yourself when your voice is at its baseline. Keep a record of the baseline measurements for later comparison. Any sudden or persistent variance from baseline measurements or from the norms may warrant medical attention.

1. Speaking Fundamental Frequency

Speaking fundamental frequency is the average pitch at which one speaks. Norms have been developed to determine average speaking pitch as influenced by a person's age and gender. A significant lowering of your average speaking fundamental frequency may indicate vocal fold pathology. In order to determine your speaking fundamental frequency:

- Say "mm-hmmm" several times

- Say "mm-hmmm" a last time and sustain the "mmm"

- Match the pitch of your "mmm" to a pitch played on well-tuned piano or other musical instrument

- Record the name of that matching pitch; this is your speaking fundamental frequency.

The following speaking fundamental frequency norms have been provided as a result of Dr. Daniel R. Boone's work published in 1991:

Women

Men

Women

Men

21

21

51

51

G below middle C

C below middle C

F below middle C

A2 (8 notes below middle C)

2. Maximum Phonation Time

Maximum phonation time is a measurement of respiratory and sound control. Using a watch with a second hand, hold an "ah" for as long as you can and record the duration in number of seconds. Adults should typically be able to hold a quiet sound for 15 - 20 seconds; time significantly less than this may indicate vocal fold pathology (Boone, 1991).

3. Vocal Range

Vocal range describes the scope of sounds ranging from high pitches to low pitches that your voice can produce. Using a piano, identify the highest and lowest notes you can sing. You may use any vowel that is comfortable for you. Keep in mind that this does not necessarily indicate your functional singing range. The sounds may not be the most pleasurable to hear; however, these sounds identify how fast your vocal folds can potentially vibrate under normal conditions. In general, singers and healthy speakers should have between 18-24 whole notes in their vocal range; anything less may suggest vocal fold pathology.

4. Vocal Fold Efficiency or S:Z Ratio

Hold the hiss of a soft "ssss" sound for as long as you can on a single breath. Measure the duration in seconds. Repeat with a soft "zzzz" sound and compare the two durations. This measures how efficient the vocal mechanism is by comparing voiceless (open vocal folds) and voiced (closed vocal folds) sounds. Ideally, one should be able to hold each sound for an equal duration, indicating that the vocal folds are valving air effectively. Simply put, the ratio should be 1:1, meaning one should be able to hold both the /s/ and the /z/ for equal amounts of time. If the two durations are very different, this may be an indication of vocal fold pathology. For example, if a person could hold an /s/ for 20 seconds and a /z/ for 10 seconds, the vocal folds are inefficiently closing, wasting air.

5. Happy Birthday Task

Another practical measure of vocal health may be determined by singing "Happy Birthday" as quietly as possible in the upper third of your personal vocal range. First you must determine your full vocal range (see above). Divide your range into thirds, and locate the first note of the uppermost third of your range. Use this pitch as your starting pitch each time. If on a given day you cannot sing this tune without excessive breathiness, difficulty starting the sound, or voice "breaks," there is a good chance that vocal fold swelling may be present from overuse, acid reflux, abusive coughing, or a host of other causes of intermittent vocal fold swelling. Regardless of cause, vocal fold swelling indicates that it is not a good day to sing. When vocal fold swelling is indicated use judicious vocal rest (increasing silence with relaxed and gentle speaking only as necessary). Judicious vocal rest allows the troublesome swelling to subside (Bastian, Keidar, & Verdolini-Marston, 1990).

Laryngeal Stroboscopy

Laryngeal stroboscopy is one of the most useful and state-of-the-art techniques currently available for the examination of the larynx. At the Milton J. Dance, Jr. Head and Neck Center, the laryngeal stroboscopy examination is performed jointly by a physician and a speech pathologist.

Frequently Asked Questions about Laryngeal Stroboscopy

What happens during the evaluation?

Step 1: You will first be asked to complete a questionnaire regarding the onset of your voice problem, your medical history and current medications, current voice demands, and any specific symptoms related to your voice problem.

Step 2: A speech pathologist will guide you in performing simple vocal tasks using a microphone. Computer analysis of your vocal quality will then be performed.

Step 3: The physician may spray a topical anesthetic in your throat for your comfort during the procedure. (Note: Please inform the physician if you have had any reactions to anesthesia in the past.)

Step 4: The physician will insert a small endoscope through your mouth towards the back of your tongue. The endoscope provides a telescopic video recording of your larynx. The speech pathologist will then ask you to perform various voice tasks in order to observe the movement of your vocal cords and the condition of your larynx.

How long will it take?

The entire evaluation may take approximately thirty minutes to one hour; however, the total time that the endoscope is in your mouth is only approximately two minutes.

When will I receive the results?

Immediately following the evaluation, the physician and speech pathologist will review your results and provide recommendations which may include one or all of the following: referrals, medication, voice therapy, and/ or surgery.

How do I need to prepare?

There is no preparation required for the procedure. You may eat and drink as you wish. Please arrive 15 minutes prior to the appointment to complete the necessary paperwork.

Reflux Changes to the Larynx

Acid Reflux and the Larynx

What is acid reflux disease and what are the symptoms?

Gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, is the recurring movement of stomach acid from the stomach back up into the esophagus (Gaynor, 1991). Stomach acid in the esophagus may cause heartburn or even chest pain; however, not all individuals will experience heartburn as the esophagus is capable of withstanding a certain amount of acid exposure. On the other hand, the throat and larynx (voicebox) are not meant to withstand any exposure to acid. If acid actually refluxes into the lungs, chronic cough and pulmonary conditions can result, such as pneumonia or bronchitis.

Acid reflux into the larynx and throat is often referred to as "laryngopharyngeal reflux," or LPR. Symptoms of acid reflux into the larynx may include laryngitis, hoarseness, sensation of a lump in the throat, post-nasal drip, chronic throat clearing, excessive throat mucous, sore throat, cough, laryngospasm (spasm of the throat), and/ or throat pain (Gaynor, 2000). With particular regard to singers and professional voice users, other symptoms may include increased time necessary to achieve adequate vocal warm-up, restricted vocal tone placement, and decreased pitch range (Ross, Noordzji, & Woo, 1998).

How does acid reflux happen?

Understanding how acid reflux occurs is crucial in understanding how to avoid it. At the end of the esophagus is a tight muscle, known as the "lower esophageal sphincter," or LES. This muscle is intended to relax only as food passes from the esophagus into the stomach. Reflux can occur when the pressure or tightness of this muscle is decreased. Certain substances and behaviors are linked to the lowering of pressure of the LES. According to Gaynor (1991), diets high in fat and carbohydrates, alcohol consumption, and the use of tobacco products may all result in a susceptibility to reflux. Carminatives (peppermint and spearmint) may also decrease LES pressure; therefore, conservative use of mint-flavored gums and candies may be well-advised for individuals with reflux.

In the work of Wong, Hanson, Waring, & Shaw (2000), acid reflux was often found to occur with belching or when lying down after meals. To avoid this risk, individuals suffering from acid reflux should avoid carbonated beverages, which lead to belching, and should avoid eating two hours before lying down. Individuals with acid reflux may also have delayed emptying of the stomach in the lower intestinal tract, leaving increased amounts of food in the stomach. The more food there is in the stomach, the more time will be needed to allow for gastric emptying, and the higher the potential for more acid to be refluxed (Gaynor, 1991). To address this, it is often recommended that one have several small meals throughout the day rather than three large meals.

Certain behaviors also linked to lowered LES pressure include increased intra-abdominal pressure and bending over, creating an increased possibility for reflux (Gaynor, 1991). Forceful abdominal breathing during singing and strenuous workouts (which often involve bending over) can each contribute to lowered LES pressure. Since certain types of breathing and stretching both contribute to positive vocal use, singers and professional speakers suffering from GERD might discuss with their physician the merits of taking antacids prior to performances and/or physical workouts to neutralize any acid that might be refluxed.

How does acid reflux affect my voice?

Acid reflux into the larynx occurs when acid travels the length of the esophagus and spills over into the larynx. Any acidic irritation to the larynx may result in a hoarse voice. As the vocal folds begin to swell from acidic irritation, their normal vibration is disrupted. Even small amounts of exposure to acid may be related to significant laryngeal damage.

This disruption in the vibratory behavior of the vocal folds will often produce a change in the singing or speaking voice. When a singer or speaker encounters an undesirable vocal sound, the first impulse is to compensate by unknowingly changing the way in which one is singing or speaking. If the negative vocal results of acid reflux are addressed by a compensatory change in vocal technique, functionally abusive vocal behaviors often develop and can exacerbate the original symptoms through excessive muscular tension or even contribute to the development of vocal fold pathologies. For more detailed information on compensatory vocal behaviors, see an article by Dr. Jamie Koufman and Dr. Peter Belafsky entitled The Demise of Behavioral Voice Disorders.

Reflux of acid into the larynx can have a detrimental effect on the voice for several reasons, as mentioned above. One unusual phenomenon has been observed whereby irritation found only in the lower esophagus can stimulate abnormal muscular contractions in the larynx such as coughing or throat clearing via shared nerved impulses between the esophagus and the larynx (Gaynor, 1991; Shaw & Searl, 1997; Wong, Hanson, Waring, & Shaw, 2000). As a result, individuals with acid reflux may have a persistent cough in the absence of any direct contact between stomach acid and the larynx. Persistent coughing can lead to vocal fold lesions, which in turn will negatively affect vocal quality and performance.

Individuals reflux stomach acid as a result of several factors, including hiatus hernia (malfunction of the stomach valve), obesity (being overweight), and poor eating habits. Poor eating habits, which can make reflux worse, include night eating, overeating, and consuming food or drinks that promote stomach acid production, such as spicy, fatty, or fried foods, acidic foods (tomato sauce, orange juice), soda, coffee, tea, chocolate, mints, and alcohol. In addition, using tobacco products in any form promotes stomach acid production.

How can reduce my risk of acid reflux?

To reduce the likelihood of reflux, and to improve your condition, you may adhere to the following guidelines:

- No eating or drinking within three hours of bedtime or lying down to rest. This includes lying down anytime, such as an afternoon nap. Individuals suffering from reflux may have delayed emptying of the stomach in the lower intestinal tract, leaving increased amounts of food in the stomach. The more food there is in the stomach, the higher the potential for more acid to be refluxed (Gaynor, 1991). As a result, added time will be needed to allow for gastric emptying. If circumstances dictate that one must eat late, the lighter and lower in fat the food, the quicker the stomach will empty into the intestinal tract.

- Avoid overeating. Overfilling the stomach increases the likelihood of reflux. It is better to eat several small meals each day than to eat one or two big meals.

- Avoid intra-abdominal pressure. Avoid tight-fitting clothing, bending over, or straining after eating (especially working out and lifting weights).

- Reduce your intake of foods that increase stomach acid production. These include fatty, fried, spicy, or acidic foods, chocolate, caffeine, carbonated beverages, peppermint/ spearmint, and alcohol.

- Elevate the head of your bed. Place cinder blocks under the legs at the head of your bed. This will put the bed at an incline of at least 5 inches.

- Lose weight. You should lose weight if you are overweight; excess weight puts pressure on gastric contents.

- Stop the use of any tobacco products. Good for you all around.

- Take your medication. You may be placed on a medication to control your acid production. It is important to take these medicines as instructed; however, it has been shown that the medications most commonly prescribed for acid reflux, called proton pump inhibitors, are most effective if taken 30 - 60 minutes prior to your most substantial meal (usually dinner).

- Use over-the-counter antacids. Over-the-counter antacids may be appropriate, especially if you will be singing or eating close to bedtime. If you are advised to take antacids, chewable antacids such as Rolaids and Tums are not recommended because they do not neutralize enough stomach acid to be effective. You may add a medication called an H2 blocker to your daily routine, such as Zantac or Pepcid, before singing or exercising and before bed. You may also use liquid antacids such as Maalox, Mylanta, Geluscil, Amphogel, or Gaviscon. Take these as instructed.

- Chew your gum! New research from Great Britain shows post-meal gum chewing appeared to reduce acid in the esophagus and quell heartburn symptoms among people with chronic reflux problems. Why does it work? Gum stimulates saliva production, which theoretically works to neutralize acid remaining in the larynx and esophagus.

- Sleep on your left side. The esophagus enters the stomach on your right side. Sleeping on your left side may help to prevent any food remaining in your stomach from pressing on the opening to the esophagus, which could cause reflux.

In summary, acid reflux affects many voice users, some of whom may be unaware that the source of their vocal difficulty is medical and can be addressed with the options listed above. If you think you may suffer from acid reflux, there is no danger in following the behavioral and dietary guidelines above, but a visit to a qualified medical professional is the only means of securing an accurate diagnosis. Some physicians who do not specialize in voice disorders may be unaware of the relationship between acid reflux and hoarseness, and the symptoms of acid reflux may be easily attributed to other illnesses or poor vocal techniques. Be sure to question your medical professional to be certain that the possible diagnosis of acid reflux is not overlooked.

References

- Gaynor E.B. (1991). Otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 86(7), 801-808.

- Gaynor, E.B. (2000). Laryngeal complications of GERD. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 30(3 Suppl), S31-34.

- Ross, J.A., Noordzji, J.P., & Woo, P. (1998). Voice disorders in patients with suspected laryngo-pharyngeal reflux disease. Journal of Voice, 12(1), 84-88.

- Shaw, G.Y. & Searl, J.P. (1997). Laryngeal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux before and after treatment with omeprazole. Southern Medical Journal, 90(11), 1115-1122.

- Wong, R.K., Hanson, D.G., Waring, P.J., & Shaw, G. (2000). ENT manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux.

- American Journal of Gastroenterology, 95(8 Suppl), S15-22.

Fender Music and Voice Studio

Singing the Praises of the Johns Hopkins Voice Center at GBMCThe Johns Hopkins Voice Center located at GBMC's Milton J. Dance, Jr. Head & Neck Surgery Center is hitting the right notes as it mends damaged voices with a little help from Fender Musical Instruments Corporation. Read the full article featured on The Baltimore Sun.

GBMC center offers relief for voice, swallowing issues Johns Hopkins Voice Center is newest GBMC addition Elementary school teacher Theresa Wenck is finding her singing voice again inside a brand new studio on the hospital's campus. Over the winter, chronic laryngitis led to a more serious diagnosis for the chorus teacher, who was constantly singing and talking over her students. "I learned that I had a vocal hemorrhage that should have repaired itself with vocal rest, but unfortunately I needed to have surgery," Wenck said. She went to the Johns Hopkins Voice Center at GBMC, the newest addition to a comprehensive treatment facility that provides a one-stop shop for patients of all ages suffering from voice or swallowing issues. For the musicians, they can come sit in our music room, playing whatever instrument they want while they're singing and show us whatever problem they're having. Same thing for our music teachers," said laryngologist Dr. Kenneth C. Fletcher. LEARN MORE

New Treatment Center At GBMC Mending Broken VoicesMending broken voices. That’s the specialty of a new treatment center opening at GBMC. This music studio is only one part of the Johns Hopkins Voice Center at GBMC. There’s also high-tech medicine. “The idea is showing the patient this is what your vocal chords look like,” said Dr. Chuck Fletcher, Johns Hopkins Voice Center. “Your voice is just this great instrument, but it’s complicated and certainly can go bad in different ways.” LEARN MORE

Tips for Professional Voice Users

Professional voice users, including both speakers and singers, can follow particular guidelines to promote optimal vocal fold health and function.

- Consult an Ear, Nose, and Throat Doctor (ENT). Consult an otolaryngologist, or ENT, to obtain a baseline evaluation of your voice when you are healthy. Establishing a healthy picture of your larynx serves as a source of comparison if you encounter voice difficulties in the future. Search for an otolaryngologist by name, location, or subspecialty through the American Academy of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. For a listing of voice centers nationwide, please see our National Voice Center Referral Database.

- Maintain adequate hydration. Many physicians and clinicians propose that consuming approximately 64 ounces of non-alcoholic fluids per day is necessary to maintain adequate hydration. Research supports that adequate hydration allows vocal cords to vibrate with less "push" from the lungs, especially at high pitches. In addition, well-hydrated vocal cords resist injury from voice use more than dry cords, and recover better from existing injury than dry cords. Increased systemic hydration also has the benefit of thinning thick secretions. (Titze, 1988; Verdolini-Marston, Druker, & Titze, 1990; Verdolini, Titze, & Fennell, 1994; Verdolini et al., 2002; Titze, 1981; Verdolini-Marston, Sandage, and Titze, 1994).

Individuals who experience external dehydration, such as those individuals living or working in a very dry environment, may benefit from the use of a humidifier or vaporizer. Dr. Katherine Verdolini of the University of Pittsburgh Voice Center recommends the use of a hot water vaporizer versus a cool-mist device. The reason is that cool-mist devices vaporize everything in their reservoirs, including any chemicals or germs. On the other hand, hot water vaporizers create vapor by boiling water, and because water has a lower boiling point than most chemicals, only water is delivered into the air. It is important to check with your doctor before beginning any hydration program. Drinking large quantities of water can be harmful for some individuals with serious health conditions. - Always warm-up and cool-down. Warming-up the voice is important before prolonged speaking or any singing engagements. A simple, yet effective vocal warm-up is to perform lip-trills while gliding up and down the full extent of one's pitch range. Additional exercises are discussed on the Vocal Warm-Ups page. Although frequently ignored, vocal cool-downs may also be used to prevent damage to the vocal cords. The simple practice of gentle and relaxed humming can serve as one excellent, easy form of cooling-down.

- Know your range. Avoid singing pieces at the extremes of your vocal range. To determine your range, perform light glides or lip trills to your highest and lowest notes. Record these notes by checking them on a piano. Make sure that pieces in your repertoire fall above the lowest and below the highest extremes of your range. To view average vocal ranges for soprano, mezzo soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, and bass voices, see those put forth by the New Harvard Dictionary of Music

- Know the potential side effects of your medications. Many commonly prescribed medications can have significant effects on the voice. For a listing of medications and potential adverse effects on the voice, see the list compiled by the National Center for Voice and Speech.

- Screen yourself daily for vocal cord swelling. Screening yourself for potential vocal cord swelling will help you to determine whether you should perform on a particular day, or take a vocal rest. Tasks for daily screening are found on the Vocal Screening page.

- When singing with a band, use monitors. Have some small speakers facing you on stage so you can hear yourself adequately and modify your volume accordingly.

- Avoid vocally abusive behaviors.

- Decrease overall volume.

- No shouting/ yelling.

- Don't whisper! It may actually make your voice worse.

- Don't talk in the presence of a lot of background noise! Talk to someone only when they are an arm's length away.

- Don't try to talk or sing when you have a bad cold or laryngitis.

- Avoid behaviors that may exacerbate acid reflux. Certain behaviors and foods may exacerbate acid reflux and yield poor vocal performance. Please see the page on Reflux Changes to the Larynx for more information and suggestions for modifications to reduce reflux.

- Consider speaking voice training. There is often a discrepancy between singing voice and speaking voice. Even a trained singer may demonstrate excellent technique during sung performance, but exhibit abusive speaking habits, undermining vocal functioning. To ensure a healthy balance of the entire voice, regardless of whether speaking or singing, singers may benefit from speaking voice training from an acting coach or a speech-language pathologist.

- Don't smoke! Don't smoke! Don't smoke! We can't say it enough.

Resources on the Larynx

American Academy of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery

A great source of information on the ears, nose, throat and related structures of the head and neck. Updates and fun facts about the specialty of otolaryngology, resources, and current research. Search for an otolaryngologist by name, location, or subspecialty!http://www.entnet.org

The National Center for Voice and Speech

Dedicated to studying the powers, limitations, and enhancement of the human voice and speech. Choose from the menu of short, single-topic voice research columns about the singing voice or check out Dr. Ingo Titze's top vocal warm-ups for singers!http://www.ncvs.org/

The National Association of Teachers of Singing (NATS)

A nonprofit organization dedicated to encouraging the highest standards of singing through excellence in teaching and the promotion of vocal education and research. Search for a voice teacher on their Voluntary Teacher Database by location, voice type, and style of music.http://www.nats.org/

The Voice and Speech Trainers Association (VASTA)

An international organization that serves the needs of voice and speech teachers and students in training and practice. They encourage and facilitate opportunities for ongoing education and the exchanging of knowledge and information among professionals in the field. Search for a voice coach by location.http://www.vasta.org/

Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary

Look up any musical term, listen to audio samples, take quizzes, and view simulations on this comprehensive site of musical terminology!http://dictionary.onmusic.org/

Entertainer's Secret Throat Relief

Entertainer's Secret Throat Relief is a spray formulated to resemble natural mucosal secretions and designed to moisturize, humidify, and lubricate the mucous membranes of the throat and larynx.http://www.entertainers-secret.com

Laryngology Grand Rounds

National Referral Database

This list consists of physicians and specialists who have designated themselves as competent in the area of the treatment of voice disorders. The Johns Hopkins Voice Center has no first-hand knowledge of the extent of their interest in treating voice disorders. It remains the users responsibility to evaluate their talents for caring for you. The American Academy of Otolaryngology also maintains a database of physicians who may list laryngology as their subspecialty. Please contact the Webmaster for changes to the National Referral Database.

VIEW THE NATIONAL REFERRAL DATABASE

Related Services

Head and Neck Surgery

6569 N. Charles St. Pavilion West, Suite 401 - Towson, MD 21204

Milton J. Dance, Jr. Head and Neck Center

6569 N. Charles St. Pavilion West, Suite 401 - Towson, MD 21204

Head and Neck Multidisciplinary Team

6569 N. Charles St., Pavilion West, Suite 401 - Towson, MD 21204