Head and Neck Surgery Thyroid & Parathyroid Surgery

Diagnosing and treating the full range of thyroid and parathyroid diseases

Request a Phone Consultation

A head and neck surgeon will call you within 2-3 business days. Discuss your concerns with one of our specialists at your convenience. CLICK HERE TO SCHEDULE

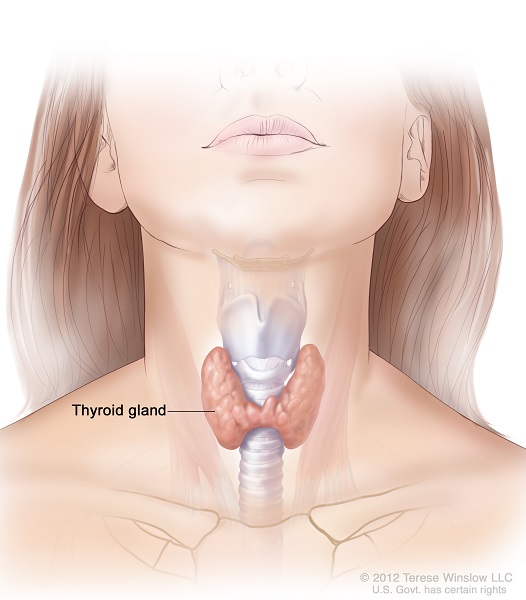

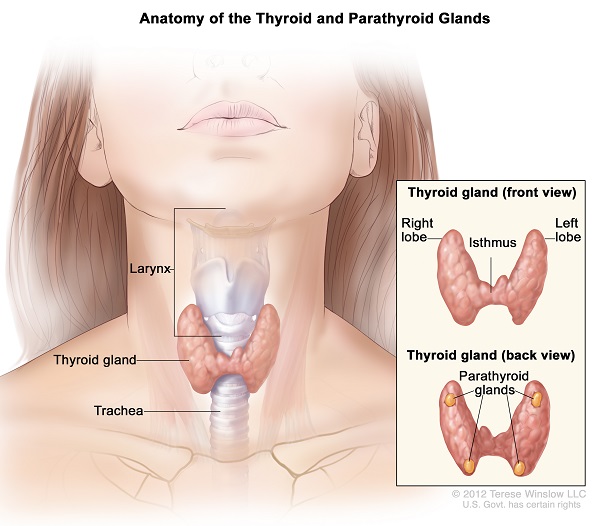

Anatomy of the Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands

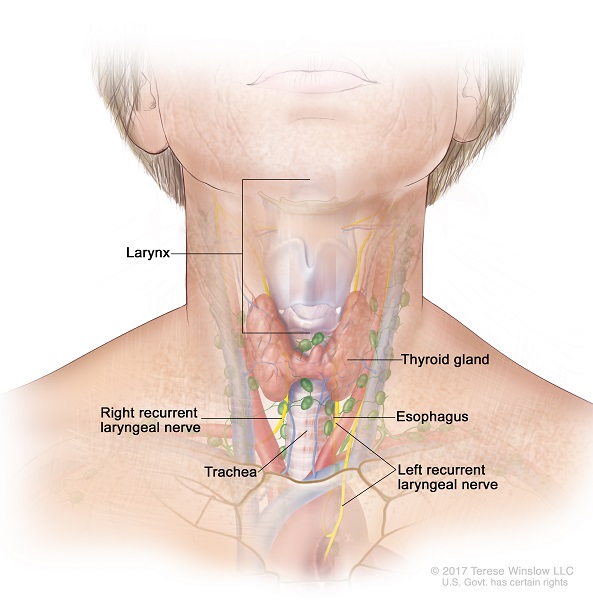

The thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped organ that sits in front of your windpipe (trachea) below the Adam’s apple (also known as the thyroid cartilage). It has two lobes, right and left, which are connected in the middle by a bridge of thyroid tissue called the isthmus.

The thyroid gland sits next to four critical structures:

- Windpipe (trachea),

- Swallowing tube (esophagus)

- Nerves to the voice box (recurrent and superior laryngeal nerves)

- Parathyroid glands

There are four parathyroid glands, two on each side, that are nestled right up against the thyroid gland. Their job is to make a hormone that helps control your calcium levels in your body. The image to the right shows the butterfly shaped gland sitting on the windpipe.

The main nerve to the voice box, called the recurrent laryngeal nerve, sits underneath the thyroid gland and on top of the swallowing tube (esophagus). Because of its location, it is at risk during surgery. If hurt or damaged, a patient’s voice can be damaged.

The thyroid gland produces a hormone that controls your body’s metabolism. If you have too much thyroid hormone in your body (hyperthyroidism), then you can have unexpected weight loss, heat intolerance (feeling hot all the time), palpitations, nervousness, tremors, or difficulty with sleep. If you have too little thyroid hormone in your body (hypothyroidism), then the opposite happens: unusual weight gain, cold intolerance (feeling cold all the time), decreased energy, difficulty with sleep, and even depression and mood disorders. Thyroid hormone imbalances can be evaluated by a simple blood test (thyroid stimulating hormone test, also known as “TSH”).

The parathyroid gland is in close approximation with the thyroid gland; however, its function is different from the thyroid gland. There are four parathyroid glands. It is located behind the thyroid lobes. The right superior parathyroid gland is located in the region of the right upper pole of the thyroid gland, and the right inferior parathyroid gland is located in the region of the right inferior pole of the thyroid gland. This configuration also occurs in the left parathyroid glands. The parathyroid shares its blood supply with the thyroid gland, but it is supplied mainly by the inferior thyroid artery.

The parathyroid gland produces hormones, namely parathyroid hormones (PTH), which are responsible for calcium and phosphate metabolism and homeostasis. PTH is also responsible and facilitates Vitamin D synthesis and calcitriol in the kidneys.

Hyperparathyroidism occurs when there is an over secretions of parathyroid hormone and with elevated calcium levels. There are three types of Hyperparathyroidism.

Primary Hyperparathyroidism- is caused by abnormalities in the parathyroid gland. It can be caused by adenoma, hyperplasia, and cancer on rare occasions. Primary Hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of elevated calcium levels. The laboratory values show high calcium, elevated PTH, and low phosphate. In 85-90 % of cases, the primary Hyperparathyroidism is caused by an adenoma, which can be surgically removed. Hyperplasia is often associated with multiple endocrine neoplasias (MEN). MEN 1 has tumors of the parathyroid gland, pituitary gland, and pancreas. MEN 2 is characterized by medullary thyroid cancer, parathyroid hyperplasia, and pheochromocytoma. Patients with excessively elevated calcium levels can present symptoms related to Bones (osteoporosis, bone fractures), Stones (kidney stones), Moans (abdominal pain, constipation, peptic ulcer, nausea, pancreatitis), Groans (muscle weakness), and Neurologic-psychiatric symptoms(fatigue, memory loss, depression, delirium).

Secondary Hyperparathyroidism- is over secretion of PTH due to low calcium levels due to disease processes like vitamin D deficiency, gastrointestinal malabsorption, and renal failure.

Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism- is rare and is associated with elevated PTH even after the causes of Hyperparathyroidism have been corrected.

Benign Thyroid Disease

Key Points

• Thyroid nodules are lumps that can form anywhere in the thyroid gland

• Vast majority of nodules are benign

• Nodules can cause symptoms when they press on nearby structures, such as the swallowing tube (esophagus), windpipe (trachea), voice box (larynx), or the nerve to the vocal cord (recurrent laryngeal nerve)

• Risk of cancer depends on patient’s history, exam, and ultrasound findings

• Fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is used to distinguish benign from cancerous nodules

• Surgery is used to remove cancerous nodules, nodules that are causing symptoms, or nodules with biopsy results that are repeatedly inconclusive

Thyroid nodules are lumps that can form anywhere in the thyroid gland. They are often found by the patient or their doctor when examining their neck. Other times and very commonly these days, they are picked up “incidentally” on CT, MRI, or ultrasound scans done for other reasons such as neck pain or chest problems. While the vast majority (over 90%) of thyroid nodules are benign, they can cause problems in one of three ways.

First, they can produce too much thyroid hormone (causing “hyperthyroidism”). The thyroid hormone is the hormone that determines your metabolism. If you have too much thyroid hormone in your body, then you can have unexpected weight loss, heat intolerance (feeling hot all the time), palpitations, nervousness, tremors, or difficulty with sleep. Hyperthyroidism can be evaluated by a simple blood test (thyroid stimulating hormone test, also known as “TSH”).

Second, a thyroid nodule can cause symptoms by pushing or pressing on nearby structures. The thyroid gland sits on the voice box, windpipe, esophagus (swallowing tube), and the nerve that controls the vocal cord (recurrent laryngeal nerve). If a nodule gets too big, it can compress these structures causing difficulty swallowing, difficulty breathing, the sensation that something is stuck in the throat, or changes in the voice such as a raspy voice. If big enough, it will be seen easily through the skin and look like an unsightly lump in the neck.

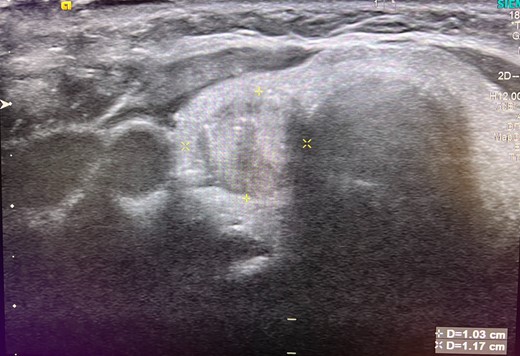

Third, some thyroid nodules are cancerous. There are risk factors for a nodule having cancer. One of the most important is a history of radiation to the neck to treat another problem such as lymphoma or head and neck cancer. Other risk factors include having a paralyzed vocal cord or a family history of thyroid cancer. We also get a sense of the risk of a nodule having thyroid cancer on the ultrasound scan. Ultrasound use soundwaves to visualize the anatomy of the thyroid and neck. This is safe and harmless, and is the same technology used to check on pregnancies. On ultrasound, cancerous nodules look differently. For example, they will be larger and look less like a simple “cyst.” They can have calcium deposits (“calcifications”). The borders of the nodule may be irregular or not smooth (“irregular margins”). The nodule can also be taller-than-wide or extend outside the thyroid gland (“extrathyroidal extension”). All of these features increase the risk of the nodule having cancer.

In order to find out whether a thyroid nodule has cancer, a biopsy is needed. The American Thyroid Association (ATA) does not recommend a biopsy for nodules smaller than 1 cm, as the chance of finding a clinically meaningful result is exceptionally small. At our thyroid center, the preferred way of biopsy is ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA). The ultrasound machine is used to visualize the nodule, and then a needle is placed into the nodule directly under ultrasound visualization, confirming that it is in the right place in real time. The needle “aspirates” or sucks up cells of the nodule, which are then placed onto a slide. This is then sent to our pathologist colleagues to analyze using a microscope. The turnaround time for the final result is typically a week or less. If needed, we prefer to do the biopsy on the same day and same rooms as our clinic appointment, so we do not waste your time with multiple visits. Occasionally, the FNA biopsy result is inconclusive or indeterminate. In these settings, we often repeat the biopsy and/or perform molecular testing (eg Veracyte Affirma, Thyroseq, etc), which can give more information on the risk for cancer.

Ultrasound of the thyroid showing a 1.2 cm nodule of the right thyroid lobe.

Needle entering thyroid nodule under ultrasound-guidance for fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy.

The biopsy results are reported using the Bethesda Classification System. In this classification, there are six categories. The first is termed “nondiagnostic,” meaning that the biopsy sample is insufficient for the pathologist to make any judgment on it. The second category is “benign.” The risk of cancer with this result is less than 3%. The third category is called “atypia of undetermined significance” (AUS) or “follicular lesion of undetermined significance” (FLUS). This result means the biopsy sample has enough cells for analysis, but the pathologist cannot say whether the nodule is benign or cancerous. In technical terms, the biopsy is “cytologically indeterminate.” The risk of cancer in this category is 5-15%. The fourth category is “follicular neoplasm”. Like AUS/FLUS, the biopsy sample is adequate, but we cannot say whether it is benign or cancerous, and it is therefore also “cytologically indeterminate.” The risk of cancer in this category is 25-40%. The fifth category is “suspicious for malignancy.” The risk of cancer in this category is 50-75%. The sixth and final category is “malignant,” and the probability of cancer is over 97%. The fifth and sixth categories are considered cancer and should be treated accordingly.

For “cytologically indeterminate” biopsy results, which are Bethesda categories 3 and 4 (AUS, FLUS, and follicular neoplasm), there are three options on what to do next. First, the FNA biopsy can be repeated and/or molecular testing done on the biopsy sample. These molecular tests, such as Affirma or Thyroseq, examine the biopsied cells for mutations known to be involved in thyroid cancer. These results can help us better understand the risk for cancer in the biopsy, either putting us at ease or increasing our suspicion. The second option is to closely watch the nodule with repeated ultrasound examinations. The idea is that if the nodule has cancer, then it will change over time and declare itself. This is appropriate for patients without risk factors or the possibility of an aggressive cancer. The final option is to remove the thyroid lobe with surgery (“diagnostic lobectomy”) to put to rest any doubt as to what the thyroid nodule is. This has the added benefit of removing it should it be cancerous. The disadvantage, obviously, is that it is a surgery with potential risks.

Over time, around 15% of benign nodules will become smaller, 15-20% become bigger, and the remainder stay the same. Surgery is used to remove a thyroid nodule when they are causing symptoms or if there is a risk for cancer with inconclusive FNA biopsy findings.

Key Points

• Thyroid goiter is the term for an abnormally enlarged thyroid gland

• In developing countries, goiters are usually caused by iodine-deficiency

• In the United States, goiters are usually caused by enlarged nodules, Grave’s disease, or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

• Goiters cause symptoms when they press on nearby structures, such as the swallowing tube (esophagus), windpipe (trachea), voice box (larynx), or the nerve to the vocal cord (recurrent laryngeal nerve)

• Smaller goiters that are not causing symptoms can be carefully watched

• Large goiters that cause symptom should be removed by surgery

Thyroid goiter is the medical term for an abnormally enlarged thyroid gland. Goiters are usually large enough where it is noticed easily by friends and family as a swelling in the neck. Historically, the most common cause of goiters was a lack of iodine in the diet. Iodine is an essential component of the thyroid hormone that the gland makes. When there is insufficient iodine in the body, the gland becomes goitrous as it struggles to work with the iodine deficiency. This is still common in the developing world.

In the United States, this is not as common, since iodine is routinely added to our table salt. Instead, goiters in the United States are more likely to be caused by autoimmune diseases. Autoimmune diseases are when the body’s immune system incorrectly attacks its own body tissue, causing inflammation and dysfunction of the organ affected. In the thyroid, two very common autoimmune diseases are Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Grave’s disease. The increased inflammation from the autoimmune attack on the thyroid causes it to become hypervascular, engorged, and swollen. On ultrasound, we often see nodules in the gland with these conditions. These autoimmune diseases can be diagnosed by simple blood tests. Thyroid goiters can also be caused by a very large single nodule or multiple nodules (“multinodular goiter”) without autoimmune disease.

Thyroid goiters cause problems in several ways. First, if due to an autoimmune disease, the thyroid goiter can be associated with too little thyroid hormone (“hypothyroidism”) or too much thyroid hormone (“hyperthyroidism”). The thyroid hormone is the hormone that determines your metabolism. If you have too much of it in your body, then you can have unexpected weight loss, heat intolerance (feeling hot all the time), palpitations, nervousness, tremors, and difficulty with sleep. If you have too little thyroid hormone, then the opposite happens: unexpected weight gain, cold intolerance (feeling cold all the time), lack of energy, and even depression. Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can be evaluated by a simple blood test (thyroid stimulating hormone test, also known as “TSH”). The second way a thyroid goiter causes problems is by its pushing on important nearby structures. The thyroid gland sits on the voice box, windpipe, esophagus (swallowing tube), and the nerve that controls the vocal cord (recurrent laryngeal nerve). Goiters can push on these structures causing difficulty swallowing, difficulty breathing, the sensation that something is stuck in the throat, or changes in the voice such as a raspy voice. Large goiters can also go into the chest from the neck, pushing on the lungs and the lower windpipe, causing even more problems with breathing.

Treatment of a thyroid goiter depends on a few things. First, if due to an autoimmune disease, medical treatment of the autoimmune disease can help the gland become smaller and prevent further growth. We work closely and coordinate with our endocrinology colleagues on this. Second, if the goiter is causing symptoms by pushing on or obstructing nearby structures, then it is best to have it removed with surgery. If the goiter is not causing symptoms and the appearance does not bother the patient, then it can be watched closely.

Key Points

• Grave’s disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) in the United States

• Grave’s disease is an autoimmune disease that can cause a goiter

• Diagnosis is made by blood tests

• Treatment consists of medication, radioactive iodine (RAI), or surgery

• The right treatment for each patient is personalized and requires careful consideration of all options

Grave’s disease is an autoimmune disease that is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism in the United States. Hyperthyroidism is the term for an overactive thyroid gland that makes too much thyroid hormone in the body, which is the hormone that controls metabolism. Autoimmune diseases are when the body’s immune system incorrectly attacks its own body tissues, causing inflammation and organ dysfunction. In Grave’s disease, the immune system makes an antibody that attaches to the thyroid gland cells, telling them to make more thyroid hormone that is needed. When a patient has too much thyroid hormone (hyperthyroidism), then there will be unusual weight loss, heat intolerance (feeling hot all the time), palpitations, nervousness, tremors, and difficulty with sleep. The antibody made in Grave’s disease also attaches to other parts in the body, such as the muscles around the eyes and the skin in the shins and ankles, causing swelling in these areas too. It is common for patients with Grave’s disease to have prominent, bulging eyes due to the inflammation and swelling of the muscles around them. The term for this is Grave’s orbitopathy.

The diagnosis of Grave’s disease is made by blood tests, first to confirm that there is hyperthyroidism and second to look for antibodies that are known to cause the disease. Often, nodules are seen on ultrasound scans in these patients. These should be evaluated and possibly biopsied as described in our thyroid nodule section.

The treatment for Grave’s disease uses a combination of medications, radioactive iodine (RAI), and surgery. The medications that are used work by slowing down the overproduction of thyroid hormone. These medications are beta blockers and thionamides. Atenolol is an example of a commonly used beta blocker, and methimazole is an example of the most commonly used thionamide. Radioactive iodine (RAI) is used to “ablate” or destroy the thyroid tissue so that it can no longer cause problems. Thyroid hormone replacement is then given by a pill that contains the normal amount the body needs. It is important to note that radioactive iodine (RAI) should not be used if you are planning on becoming pregnant in the near future. It can also make the eye swelling with Grave’s disease (“Graves orbitopathy”) worse. Often, Grave’s disease causes the thyroid gland to become a large goiter that pushes and obstructs the breathing and swallowing tubes (trachea and esophagus). In these situations because the goiter is causing problems, surgery is recommended to remove the entire thyroid gland. Surgery should also be used to remove the gland if the patient does not want to undergo radioactive iodine (RAI) or if there is significant Grave’s orbitopathy (Grave’s “eye disease”). Since there are many nuances to the treatment of Grave’s disease, it is best to come to a thoughtful decision after careful consultation with your endocrinologist and surgeon.

Key Points

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the most common cause of hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) in the United States

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease that can cause a goiter

• Diagnosis is made by blood tests

• Treatment is primarily medical in replacing the correct amount of thyroid hormone

• Surgery is used to remove goiters or nodules that may have cancer

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease that is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in the United States. Hypothyroidism is the term for an underactive thyroid gland where there is too little thyroid hormone in the body, which is the hormone that controls metabolism. Autoimmune diseases are when the body’s immune system incorrectly attacks its own body tissues, causing inflammation and organ dysfunction. In Hashimoto’s disease, the immune system attacks the thyroid gland, causing inflammation and dysfunction of the gland, ultimately leading to too little thyroid hormone being made. When a patient has too little thyroid hormone (hypothyroidism), then there will be unusual weight gain, cold intolerance (feeling cold all the time), decreased energy, difficulty with sleep, and even depression and mood disorders.

The diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is made by blood tests that show an underactive thyroid gland and the presence of antibodies known to cause the disease. Ultrasound examination of the thyroid gland often show nodules and pseudonodules. These should be evaluated and possibly biopsied as described in our thyroid nodule section.

The treatment of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is primarily medical, meaning thyroid hormone is prescribed to correct the hormone imbalance. Surgery to remove the thyroid gland is used in those cases where there is a cancerous nodule or if the gland becomes very large with a goiter. Interestingly, a recent study in 2019 showed that removing the thyroid gland in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis had the additional benefit of correcting any mood disorder (Gulvdog et al, Annals of Internal Medicine 2019).

Thyroid Cancer Overview

Thyroid cancer is generally grouped into three categories:

1. Differentiated thyroid cancer, which includes well-differentiated cancers such as papillary, follicular, and Hurthle cell cancers.

2. Medullary thyroid cancer.

3. Anaplastic or poorly differentiated thyroid cancers.

Differentiated thyroid cancers are the most common and have the best cure rate and prognosis. Medullary thyroid cancers are less common and have an intermediate prognosis. Anaplastic and poorly differentiated thyroid cancers are the most rare and very aggressive with a poor prognosis.

Key Points

• Differentiated thyroid cancer refers to papillary, follicular, and Hurthle cell thyroid cancers

• Most common type of thyroid cancer

• Arises from the thyroid hormone secreting cells of the gland

• Curable with a good prognosis

• Diagnosis is made by fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy and sometimes by surgery to remove the thyroid gland (partial or total thyroidectomy)

• Treatment is mainly with meticulous surgery, which is personalized for each patient’s situation

• Radioactive iodine (RAI) is used after surgery for cancers with a high-risk of recurrence

Carcinoma is a technical term for a type of cancer arising from the “lining” of tissues called “epithelium.” Carcinoma and cancer are frequently used interchangeably. Differentiated thyroid carcinomas is the term we give to well-defined cancers arising from the thyroid epithelial cells. Cancers from the thyroid epithelial cells that are not well-defined, but bizarre and immature-appearing on microscopic pathology are called poorly-differentiated or anaplastic thyroid cancers. This an important difference, because poorly-differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers are very aggressive and deadly. On the other hand, well-differentiated thyroid cancers are typically not aggressive and curable. Thankfully, the vast majority (95%) of thyroid epithelial cancers are of the better, differentiated type.

Differentiated thyroid cancers can be divided into papillary, follicular, and Hurthle cell cancers. Papillary thyroid cancer is the most common type, making up 85% of the cases, follicular thyroid cancers roughly 12%, and Hurthle cell and other less common types the rest. Papillary thyroid cancer also has subtypes. The most common is called the “classic variant.” The uncommon subtypes are called “tall-cell”, “hobnail”, “insular”, and “diffuse-sclerosing” variants. These are more aggressive forms of papillary thyroid cancer and are usually found out on removing the cancer with surgery.

Differentiated thyroid cancers begin as small nodules in the thyroid gland. Over time, the nodule gets bigger, causing a lump in the neck that either the patient feels or their doctor finds on examining the neck. This then leads to a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, also known colloquially as a “needle-biopsy”, that shows the cancer. Often, the nodule is very small (under 1 cm) and not felt by either the patient or their doctor. Instead, the nodule is seen on a CT, MRI, or ultrasound scan done for other reasons. These small “incidental” nodules with cancers are becoming more common these days in the United States and are called “microcarcinomas.”

The diagnosis of differentiated thyroid cancers is through fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy of the suspicious thyroid nodule. The American Thyroid Association (ATA) does not recommend a biopsy for nodules smaller than 1 cm, as the chance of finding a clinically meaningful result is exceptionally small. At our thyroid center, the preferred way of biopsy is ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA). The ultrasound machine is used to visualize the nodule, and then a needle is placed into the nodule directly under ultrasound visualization, confirming that it is in the right place in real time. The needle “aspirates” or sucks up cells of the nodule, which are then placed onto a slide. This is then sent to our pathologist colleagues to analyze using a microscope. The turnaround time for the final result is typically a week or less. If needed, we prefer to do the biopsy on the same day and same place as your clinic appointment, so we do not waste your time with multiple visits.

Needle entering thyroid nodule for fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy.

The biopsy results are reported using the Bethesda Classification System. In this classification, there are six categories. The first is termed “nondiagnostic,” meaning that the biopsy sample is insufficient for the pathologist to make any judgment on it. The second category is “benign.” The risk of cancer with this result is less than 3%. The third category is called “atypia of undetermined significance” (AUS) or “follicular lesion of undetermined significance” (FLUS). This result means the biopsy sample has enough cells for analysis, but the pathologist cannot say whether the nodule is benign or cancerous. In technical terms, this category is “cytologically indeterminate.” The risk of cancer in this category is 5-15%. The fourth category is “follicular neoplasm”. Like AUS/FLUS, the biopsy sample is adequate, but we cannot say whether it is benign or cancerous, and it is “cytologically indeterminate.” The risk of cancer in this category is 25-40%. The fifth category is “suspicious for malignancy.” The risk of cancer in this category is 50-75%. The sixth and final category is “malignant,” and then the probability of cancer is over 97%. The fifth and sixth categories are considered cancer and should be treated as such.

For “cytologically indeterminate” biopsy results, which are Bethesda categories 3 and 4 (AUS, FLUS, and follicular neoplasm), there are three options on what to do next. First, the FNA biopsy can be repeated and/or molecular testing done on the biopsy sample. These molecular tests, such as Affirma or Thyroseq, examine the biopsied cells for mutations known to be involved in thyroid cancer. These results can help us better understand the risk for cancer in the biopsy, either putting us at ease or increasing our suspicion. The second option is to closely watch the nodule with repeated ultrasound examinations (“active surveillance”). The idea is that if the nodule has cancer, then it will change over time and declare itself. This is appropriate for patients without risk factors or the possibility of an aggressive cancer. The final option is to remove the thyroid lobe with surgery (“diagnostic lobectomy”) to put to rest any doubt as to what the thyroid nodule is. This has the added benefit of removing it should it be cancerous. The disadvantage is that it is a surgery, which always comes with risks.

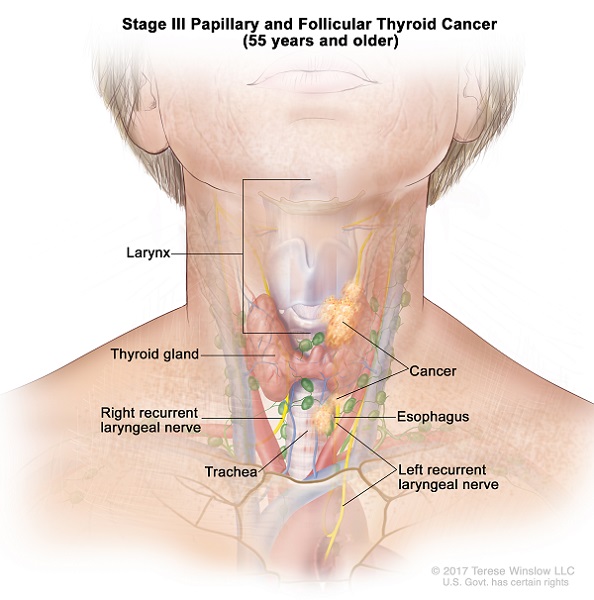

If diagnosed with differentiated thyroid cancer, an ultrasound examination is needed to look at the lymph nodes of the central and anterolateral neck. If there are abnormal appearing lymph nodes, these should be biopsied. Sometimes a CT scan of the neck is also used for additional detail. If cancer is found in lymph nodes on biopsy, then the lymph nodes in these areas should be removed with a neck dissection surgery.

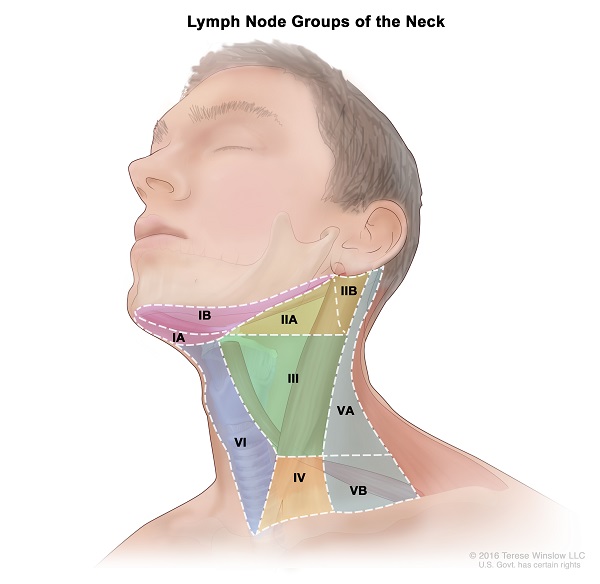

Thyroid cancers can spread to the lymph nodes in the neck. The lymph nodes or the lymphatic system are the “drainage” or “filtration” system of the body. While arteries carry blood to tissues and veins carry blood back to the heart, a small amount of fluid gets left behind and is filtered through the lymph nodes in the lymphatic system. These lymph nodes then check the fluid for bacteria and viruses and start an immune response to them if present. They also check for cancerous cells and contain them. Lymph nodes are spread out all over the body. They are typically the size of a “jelly-bean” or smaller. However, when having cancer, they become bigger and abnormal looking. In the neck, there are lymph node stations called “levels” that are labeled 1 through 7. These neck levels drain dedicated parts of the head and neck. For example, in thyroid cancer, the first place that cancer will go to is to the “central” neck levels, which are levels 6 and 7. After that, the cancer can spread to the “lateral” neck levels, which are 2-5. Thyroid cancer rarely goes to level 1 or level 2b.

Papillary thyroid cancer commonly spreads to the central and lateral neck lymph nodes. Some studies quote that up to 60% of patients have microscopic cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis! This sounds alarming at first, but let me explain why that needs to be taken with a grain of salt and put in proper context.

To understand why, it is helpful to think of cancer in the lymph nodes as either “microscopic” or “clinically-apparent.” “Microscopic” cancer in the lymph node means that the patient cannot feel the lymph node and it looks normal on ultrasound or CT scan. The cancer is found only when the lymph node is removed during surgery and the pathologist carefully looks through it for evidence of disease. “Clinically-apparent” cancer in the lymph node happens when an abnormal lymph node is apparent, meaning the lymph node is either bulky and enlarged and felt by the patient, or it looks abnormal on ultrasound or CT scan. These “clinically-apparent” lymph nodes are biopsied before surgery to confirm they have cancer in them, and then they are removed during the surgery to remove the thyroid gland. Patients who have “clinically-apparent” cancer in the lymph nodes are the ones who are at increased risk of the cancer of coming back (“recurrence”). Patients with “microscopic” cancer in the lymph nodes are usually not, with some exceptions that are beyond the scope of this website. What this means is that most patients with papillary thyroid cancer and “microscopic” cancer in their lymph nodes do very well. This is because either the “microscopic” cancer does not cause problems and remains dormant for the remainder of the patient’s life, or that the therapies that we use after surgery such as radioactive iodine (RAI) or thyroid hormone suppression treats the “microscopic” disease and eliminates it. For those patients with “microscopic” cancer in their lymph nodes that do grow and become “clinically-apparent”, a neck dissection procedure at that time to remove the lymph nodes can safely be done. It is not recommended to routinely remove the lymph nodes with neck dissection procedures for all patients with thyroid cancer, as the side effects and risks of the surgery may do more harm than good.

Follicular thyroid cancers are less likely to spread to lymph nodes than papillary thyroid cancers. Instead, they are more likely to invade blood vessels in the thyroid gland (called “vascular invasion” or “angioinvasion”) and spread to distant parts of the body, such as the lungs and bones (when this happens it is called “distant metastasis”). Distant metastases happen in 10% of cases of follicular thyroid cancer, and if this happens it is a bad sign.

Hurthle cell cancer used to be considered a variant of follicular thyroid cancer but is now recognized as a distinct rare form. Like follicular thyroid cancer, it is more likely to spread via the bloodstream (“hematogenous spread”) than papillary thyroid cancer. Unlike follicular thyroid cancer, it is also more likely to spread to the lymph nodes as well. Patients with Hurthle cell cancer do not do as well as follicular thyroid cancer.

The treatment of differentiated (papillary, follicular, or Hurthle cell) thyroid cancer is primarily with surgery. Radioactive iodine (RAI) is used afterwards for cases that are at high risk of recurrence. Chemotherapy and radiation are used in advanced cases that have recurred or spread to many parts of the body (lungs, liver, bones, etc).

There are different types of surgeries to remove thyroid cancer, including thyroid lobectomy (also known as a partial thyroidectomy), total thyroidectomy, central neck dissection (removal of the lymph nodes below the thyroid gland), and lateral neck dissection (removal of the lymph nodes to the side of the thyroid gland).

A thyroid lobectomy is removal of one-half of the thyroid gland with the cancer in it. This is recommended in differentiated thyroid cancer if the following conditions are met:

- The cancer is less than 4 cm in size.

- There are NO bad features to it. Examples of bad features include extension of the thyroid cancer outside of the thyroid gland (called “extrathyroidal extension) or if the cancer is an uncommon aggressive type (such as tall cell, columnar cell, hobnail, insular, diffuse sclerosing, Hurthle cell, etc).

- The cancer has not spread to the lymph nodes in the neck or to other parts of the body.

- There are no nodules in the other half of the thyroid gland.

The advantage of a thyroid lobectomy is that the remaining half of the thyroid gland can make enough thyroid hormone so that the patient does not need to take thyroid hormone supplement. Additionally, since only one-half of the thyroid gland is operated on, there is one-half of the surgical risk compared to a total thyroidectomy.

A total thyroidectomy is the complete removal of the thyroid gland. This is recommended when the following are present:

- The cancer is greater than 4 cm in size.

- The thyroid cancer is “high-risk” because it has bad features, such as it has grown outsize the thyroid gland (called “extrathyroidal extension”), invaded blood vessels (“vascular invasion”) or invaded the surrounding tissues such as the muscle, swallowing tube (esophagus), windpipe (trachea), voicebox (larynx) or nerve to the voicebox (recurrent laryngeal nerve).

- The cancer type is an uncommon aggressive variant, such as tall cell, columnar cell, hobnail, insular, diffuse sclerosing, or Hurthle cell, to name a few.

- The cancer has spread to the lymph nodes in the neck or to other parts of the body.

- There are nodules in the other half of the thyroid gland that does not have cancer.

The advantage of a total thyroidectomy is that it completely removes all thyroid tissue. When any of the following conditions above are present, the cancer has a higher risk of returning, and therefore it is better to not leave one half of the thyroid gland in the body. Removing the entire thyroid gland is also needed before radioactive iodine (RAI) can be given.

A central neck dissection is the complete removal of the lymph nodes underneath the thyroid gland (levels 6 and 7). These are the lymph nodes that thyroid cancer first spreads to when it moves beyond the thyroid gland. A central neck dissection should be done when:

- There are abnormal lymph nodes in the central or lateral neck that on biopsy show differentiated thyroid cancer.

- The thyroid cancer is “high-risk”, meaning it is larger than 4 cm, has grown outsize the thyroid gland (called “extrathyroidal extension”) or invaded the surrounding tissues such as the muscle, swallowing tube (esophagus), windpipe (trachea), voicebox (larynx) or nerve to the voicebox (recurrent laryngeal nerve), or is an uncommon aggressive variant, such as tall cell, columnar cell, hobnail, insular, diffuse sclerosing, or Hurthle cell, to name a few.

- The information gained from the central neck dissection is needed before deciding on whether to give radioactive iodine (RAI) after surgery. For example, radioactive iodine is recommended if more than 5 lymph nodes in the central neck have differentiated thyroid cancer in them.

A lateral neck dissection, also known as a modified radical neck dissection, or an anterolateral neck dissection, is the removal of the lymph nodes under the large muscle on the side of our neck, called the sternocleidomastoid, and are closely associated with the internal jugular vein and carotid artery. These lymph nodes should be removed only if there is biopsy-proven cancer in them.

Radioactive iodine (RAI) has been used to treat thyroid cancer since the 1940s. RAI relies on the fact that thyroid tissue uniquely takes up iodine in the body, because iodine is an essential component of the hormone that the thyroid gland makes. Furthermore, thyroid cancer cells are more likely to take up iodine than normal thyroid cells. In RAI, the iodine is modified to be radioactive, called iodine-131 or 131-I. When the thyroid cell takes up the iodine, the radioactive part of it emits radiation that then kills the thyroid cell.

In differentiated thyroid cancers, RAI is used after surgery in patients who are at increased risk of the cancer coming back (“recurring”). As mentioned previously, there are many factors that go into determining whether a patient is at increased risk of having the cancer come back. Some of these factors are listed below:

- Cancer is larger than 4 cm.

- Cancer has grown outsize the thyroid gland (called “extrathyroidal extension”) or invaded the surrounding tissues such as the muscle, swallowing tube (esophagus), windpipe (trachea), voicebox (larynx) or nerve to the voicebox (recurrent laryngeal nerve).

- Cancer is an uncommon aggressive variant, such as tall cell, columnar cell, hobnail, insular, diffuse sclerosing, or Hurthle cell, to name a few.

- Cancer has spread to more than 5 lymph nodes in the central neck or any lymph node in the lateral neck.

- Cancer has spread to a lymph node causing it to be bigger than 3 cm in size.

- In follicular thyroid cancer, there are more than four spots where it has invaded blood vessels (“vascular invasion”).

- Cancer has spread to spots beyond the neck, for example to the lungs or bone (called “distant metastases”).

- Very young or older age patient.

There are side effects to RAI. It can (uncommonly) cause swelling of the salivary and tear glands, and decrease the amount of saliva and tears a patient has after treatment. There is scientific evidence that RAI slightly increases the risk for another cancer, such as leukemia and salivary gland cancers. This is why RAI is not given routinely after every thyroid surgery. The art of medicine is a balancing act. We have to treat the disease the best we can, but we also want to avoid potential risk whenever possible. Therefore, the medical community over time has carefully identified the risk factors that warrant RAI treatment.

Patients who get RAI treatment can expose their family and friends to low doses of radiation. Therefore, to protect family and friends from radiation exposure, the patient who gets RAI should avoid close contact with another adult, pregnant woman, infant, or child. This means not sharing cups, utensils, towels etc. The amount of time that this lasts for depends on the dose of RAI given and the protocol of the doctor’s office or hospital.

Key Points

• Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) is the third most common type of thyroid cancer, yet still overall rare (~3-5% of thyroid cancers)

• Arises from the parafollicular C cells of the thyroid gland that make calcitonin

• Often hereditary; therefore all patients should have genetic screening

• Diagnosis is through fine needle aspiration (FNA) of a thyroid nodule

• Treatment is mainly with a meticulous surgical resection

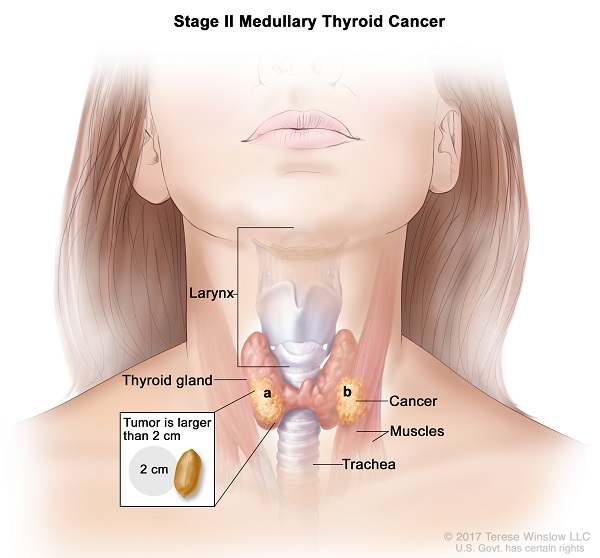

Medullary thyroid cancer is the third most common type of thyroid cancer. It arises from cells within the thyroid gland called the parafollicular C cells. The job of the parafollicular C cells is to make a hormone called calcitonin, which helps to regulate the calcium level in your body. These cells do not make thyroid hormone, and they are different from the cells that turn into differentiated thyroid cancers. This cancer is more aggressive than differentiated thyroid cancer, and the survival rates are not as good.

Medullary thyroid cancer begins as a lump or growth in the thyroid gland called a nodule. The diagnosis of medullary thyroid cancer is through fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy of a thyroid nodule. At our thyroid center, the preferred way of biopsy is ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA). The ultrasound machine is used to visualize the nodule, and then a needle is placed into the nodule directly under ultrasound visualization, confirming that it is in the right place in real time. The needle “aspirates” or sucks up cells of the nodule, which are then placed onto a slide. This is then sent to our pathologist colleagues to analyze using a microscope. The turnaround time for the final result is typically a week or less. If needed, we prefer to do the biopsy on the same day and same place as your clinic appointment, so we do not waste your time with multiple visits. Sometimes the FNA biopsy is inconclusive, and the diagnosis is made after one-half of the thyroid gland containing the nodule is removed (thyroid lobectomy).

Interestingly, one-third of patients with medullary thyroid cancer develop the cancer because of a familial or inherited genetic disease. The rest do not have this genetic mutation. Because of the high rate of the disease being inherited genetically, all patients diagnosed with medullary thyroid cancer should have genetic screening to determine whether they have the hereditary form of the cancer, even if there is no family history of the cancer.

There are well-known genetic syndromes associated with medullary thyroid cancer. These are the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes. The are many types of MEN syndromes, but the ones specifically associated with medullary thyroid cancer are MEN2A and MEN2B syndromes. In these syndromes, there are often other tumors such as pheochromocytomas (which can cause elevated blood pressure) or hyperparathyroidism (which causes elevated calcium). For this reason, we often test patients for these other tumors by measuring calcium and metanephrine levels in the blood, in addition to having genetic screening for an inherited or familial form of the cancer.

The lymph nodes or the lymphatic system are the “drainage” or “filtration” system of the body. While arteries carry blood to tissues and veins carry blood back to the heart, a small amount of fluid gets left behind and is filtered through the lymph nodes in the lymphatic system. These lymph nodes then check the fluid for bacteria and viruses and start an immune response to them if present. They also check for cancerous cells and contain them. Lymph nodes are spread out all over the body. They are typically the size of a “jelly-bean” or smaller. However, when having cancer, they become bigger and abnormal looking. In the neck, there are lymph node stations called “levels” that are labeled 1 through 7. These neck levels drain dedicated parts of the head and neck. For example, in thyroid cancer, the first place that cancer will go to is to the “central” neck levels, which are levels 6 and 7. After that, the cancer can spread to the “lateral” neck levels, which are 2-5. Thyroid cancer rarely goes to level 1 or level 2b.

Medullary thyroid cancer has a high rate of spreading to the central and lateral neck lymph nodes, approximately 70% of the time. All patients need an ultrasound of their neck to look for enlarged lymph nodes prior to surgery. Often a CT scan is done as well because it adds additional detail. Unlike differentiated thyroid cancers, when medullary thyroid cancer spreads to the lymph nodes the patient’s chance of being cured of the disease decreases significantly. Because this cancer is more aggressive than the more common differentiated thyroid cancer, a total thyroidectomy or complete removal of the thyroid gland is recommended for all patients. A thyroid lobectomy alone is not recommended. Additionally, removal of the lymph nodes underneath the thyroid gland (called a “central neck dissection”) should also be done because of the high rate of the disease spreading to the lymph nodes.

Treatment of medullary thyroid cancer is mainly with surgery. All patients should get at least a total thyroidectomy and central neck dissection. A total thyroidectomy is the complete removal of the thyroid gland. A central neck dissection is the complete removal of the lymph nodes underneath the thyroid gland (levels 6 and 7). These are the lymph nodes that thyroid cancer first spreads to when it moves beyond the thyroid gland.

The decision to remove the lymph nodes in the “lateral” part of the neck (known as “lateral neck dissection”, “anterolateral neck dissection,” or “modified radical neck dissection”) is a bit more complicated. If there are abnormal appearing lymph nodes in the lateral neck on imaging, these should be biopsied. If the biopsy shows medullary thyroid cancer, then a formal lateral neck dissection should be done to remove all the lymph nodes in those levels. Some experts recommend removing them if the calcitonin level in the blood is high. Remember that medullary thyroid cancer arises from the thyroid cells that make calcitonin. If the level of calcitonin is very high in the blood, it suggests the disease may be more widespread than initially thought. The American Thyroid Association (ATA) guideline did not a reach a consensus on this topic, but did say that a lateral neck dissection “may be considered based on serum calcitonin levels.” More details on this topic is beyond the scope of this website, but we are happy to discuss more in person if needed.

There is no role for radioactive iodine (RAI) in medullary thyroid cancer, as the cells in this cancer do not reliably take up iodine, unlike the differentiated thyroid cancers. There is a limited role for external beam radiation therapy. Chemotherapy (kinase inhibitors) are used in patients who cannot have surgery.

Key Points

• Anaplastic thyroid cancer is the least common thyroid cancer.

• Very aggressive and one of the most lethal cancer types.

• Diagnosis is by biopsy.

• Medical emergency that needs quick diagnosis, expert evaluation, and treatment by an experienced thyroid cancer surgeon.

• Treatment uses a combination of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation.

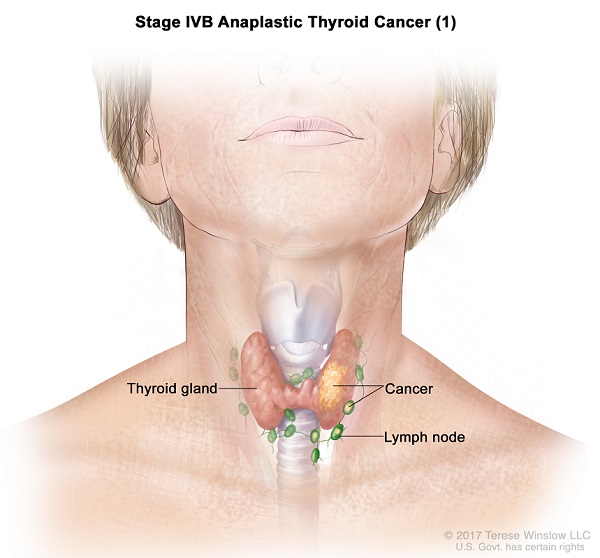

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma or cancer is the least common thyroid cancer. Carcinoma is a technical term for a type of cancer arising from the “lining” of tissues called “epithelium.” Carcinoma and cancer are frequently used interchangeably. Like differentiated thyroid cancers, anaplastic thyroid cancers arise from the lining of the thyroid gland called the thyroid follicular epithelium. Unlike differentiated thyroid cancers, which implies their being well-differentiated (see separate sections on this website), anaplastic thyroid cancers are poorly-differentiated or undifferentiated, making them very aggressive and one of the most lethal cancers in the human body. Ninety percent of patients with this cancer will die from it within one year of diagnosis. Some experts consider poorly differentiated thyroid cancers distinct from anaplastic cancer. The line distinguishing them is blurry and these diseases probably exist on a spectrum. For the purposes of this section, these types will be used interchangeably given the similarities in how they are approached and managed by doctors, knowing that some poorly differentiated thyroid cancers are not as aggressive as anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Anaplastic thyroid cancers begin as a lump or mass in the thyroid gland. Unlike the other thyroid cancers mentioned so far, anaplastic thyroid cancers grow very quickly. The patient will notice or feel a lump in the neck that is rapidly getting bigger every week. By the time they see a doctor, the cancer will have already spread to the nearby lymph nodes (regional metastasis) or even to other parts of the body like the lungs or bones (distant metastasis). By the time they see a doctor, the cancer will be causing problems in the throat by pushing on the voicebox (larynx), windpipe (trachea), swallowing tube (esophagus), or the nerve that controls the vocal cord (recurrent laryngeal nerve). Because of its rapid growth and high mortality, this cancer in many ways is a medical emergency.

Like other thyroid cancers, the diagnosis of anaplastic thyroid cancer is usually through fine needle aspiration (FNA or “needle biopsy”) biopsy. Sometimes a needle biopsy is nondiagnostic, meaning the pathologist cannot say with certainty what it is. This is because the cancer tissue has grown so rapidly and uncontrollably that sections of it have died (become “necrotic”). Necrotic tissue can be difficult to study on FNA. In these cases a larger needle biopsy (called a “core needle” biopsy) is done. Some doctors will even do a biopsy under anesthesia in the operating room and remove a larger sample (“incisional biopsy”) to ensure the right diagnosis is made quickly, given the concern for anaplastic thyroid cancer and the urgency to start treatment quickly.

Additional tests are needed after diagnosing anaplastic thyroid cancer to look for the extent of disease. These include ultrasound of the neck, CT scan of the neck, and/or MRI scan of the neck to see the extent of the cancer in the neck and the involvement of lymph nodes. A PET-CT of the whole body tests to see if the cancer has spread elsewhere in the body such as the lungs or bones. MRI brain is often done to check if cancer has spread to the brain. If the cancer has spread to distant areas in the body beyond the neck, then surgery is no longer an option in treating the cancer as it will not cure the disease and do more harm than good.

The first step in determining the treatment of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is to know its stage. The stage depends on a few aspects. First, has the cancer spread beyond the thyroid gland into nearby structures such as the windpipe (trachea), voice box (larynx), swallowing tube (esophagus), or carotid artery? Second, has it spread to the lymph nodes or other sites in the body? These aspects taken together determine the stage.

The second step is to determine if a specific mutation is present within the cancer called BRAF-V600E. Between 20-50% of anaplastic thyroid cancers have this mutation. All patient should have their cancer tested for this quickly after diagnosis. This is important because recent studies have shown that the use of medicines that inhibit this mutation can help in anaplastic thyroid cancer. These medications are dabrafenib and trametinib. Dabrafenib inhibits the BRAF-V600E mutation. Trametinib inhibits another cancer pathway seen in anaplastic thyroid cancer called the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK) pathway. When used together, they have been shown to work against anaplastic thyroid cancer.

It is also important to note that the BRAF-V600E mutation is also seen in differentiated thyroid cancer, which is a very different cancer with a much better prognosis. Just because a biopsy says that the BRAF-V600E mutation is present, it does not mean there is anaplastic thyroid cancer.

If the stage is such that the cancer can be removed safely (resectable), then it should be removed by an experienced thyroid cancer surgeon. This entails, at a minimum, removing the thyroid gland as well as the lymph nodes underneath it (central neck dissection). When removing the cancer in the thyroid gland, it is important to remove it with a cuff of normal tissue around it. This means part of the muscles of the neck, voice box (larynx), windpipe (trachea), or swallowing tube (esophagus) may have to be removed to ensure the disease has been adequately eliminated. In almost all cases of anaplastic thyroid cancer, the nerve to voice box (recurrent laryngeal nerve) has to be sacrificed because the cancer is close to it or frankly invading it. After surgery, chemotherapy and radiation are given to further increase the chance of cure.

If the cancer cannot be removed safely (unresectable) and the BRAF-V600E mutation is present, then dabrafenib and trametinib should be given to see if it shrinks the cancer and makes it resectable. If it becomes resectable after using these medicines, then the cancer should be removed by an experienced thyroid cancer surgeon as described above with chemotherapy and radiation given afterwards. If the BRAF-V600E mutation is not present in the cancer, or if the cancer does have it but does not respond to dabrafenib/trametinib, then enrollment in an experimental clinical trial should be offered where targeted medications against other mutations in the cancer can be given.

Surgical Procedures

Key Points

• Thyroid lobectomy is removal of one half of the thyroid gland and is suitable for small, low-risk cancers

• Total thyroidectomy is removal of the entire thyroid gland and is needed for higher-risk cancers

• Key structures that need to be spared during this surgery are the recurrent and superior laryngeal nerves, and the parathyroid glands

The thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped organ with two lobes (right and left). These are connected in the middle by a bridge of thyroid tissue that crosses over the windpipe (trachea) called the isthmus. A thyroid lobectomy is when one-half of the thyroid gland and the usually the isthmus are removed. The nerve that lies underneath the thyroid gland that controls the vocal cord is found during surgery, protected, and saved. This nerve is called the recurrent laryngeal nerve. It is important to save this nerve, because if injured the patient’s voice can become hoarse. Fortunately, there some procedures that can be done to improve the voice, but it will never be 100% the same as it was prior to being injured. The other important structures that need to be saved during thyroid surgery are the parathyroid glands. There are four total parathyroid glands in the body, two on each side. They are nestled up against each thyroid lobe. During a thyroid lobectomy, the parathyroid glands are carefully peeled off the thyroid lobe and saved.

During a total thyroidectomy, the entire gland is removed. The nerves that control your vocal cords (recurrent laryngeal nerves) are saved on both sides, and the parathyroid glands carefully peeled off the thyroid and saved as well. If both recurrent laryngeal nerves are injured during surgery, the patient will be unable to move their vocal cords or even an inability to breathe because of this, which becomes a medical emergency. It is important to note that an experienced thyroid surgeon can do this surgery safely without injuring these nerves. The job of the parathyroid glands is to help control your calcium level. If all of the parathyroid glands are removed during surgery, the patient can end up with permanent difficulty with controlling calcium levels in your blood, requiring lifelong medication. Occasionally after a total thyroidectomy, a patient will have temporary low calcium levels (hypocalcemia) even though all the parathyroid glands were saved. For this reason, most thyroid surgeons place their patients on supplemental calcium temporarily after surgery for 2-3 weeks.

Whenever general anesthesia is used during surgery, a tube is placed down the voice and windpipe so that the ventilator can breathe for the patient while they are under anesthesia. This tube is called an endotracheal tube and sits up against the vocal cords. During thyroid surgery, we use a special kind of endotracheal tube that is able to monitor the movement of the vocal cords. This allows the surgeon to test the nerves to the voice box (recurrent laryngeal nerve) during surgery and determine if they are functioning normally.

The decision on whether to remove half (thyroid lobectomy) or all of the thyroid gland (total thyroidectomy) depends on the cancer type and stage. Please see these respective sections on this website for more information.

Key Points

• Thyroid cancer often spreads to the lymph nodes in the neck.

• Lymph nodes or the lymphatic system are the “drainage” or “filtration” system of the body, checking for and fighting infection and cancer.

• Thyroid cancer first spreads to the lymph nodes under the gland (central neck) and then to the lymph nodes on the side of the neck (lateral neck).

• Neck dissection refers to surgical procedures to comprehensively remove these lymph nodes in cancer.

• Central neck dissection removes the lymph nodes under the thyroid gland.

• Lateral neck dissection removes the lymph nodes on the side of the neck.

Thyroid cancers can spread to the lymph nodes in the neck. The lymph nodes or the lymphatic system are the “drainage” or “filtration” system of the body. While arteries carry blood to tissues and veins carry blood back to the heart, a small amount of fluid gets left behind and is filtered through the lymph nodes in the lymphatic system. These lymph nodes then check the fluid for bacteria and viruses and start an immune response to them if present. They also check for cancerous cells and contain them. Lymph nodes are spread out all over the body. They are typically the size of a “jelly-bean” or smaller. However, when having cancer, they become bigger and abnormal looking. In the neck, there are lymph node stations called “levels” that are labeled 1 through 7. These neck levels drain dedicated parts of the head and neck. For example, in thyroid cancer, the first place that cancer will go to is to the “central” neck levels, which are levels 6 and 7. After that, the cancer can spread to the “lateral” neck levels, which are 2-5. Thyroid cancer rarely goes to level 1 or level 2b.

A central neck dissection is the complete removal of the lymph nodes underneath the thyroid gland (levels 6 and 7). These are the lymph nodes that thyroid cancer first spreads to when it moves beyond the thyroid gland. During this operation, the nerves to the voicebox called the recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLN) are traced down to where they pass underneath the carotid and innominate arteries. The lymph nodes that sit on top of this nerve and between the carotid arteries are removed in their entirety.

A lateral neck dissection, also known as a modified radical neck dissection, or an anterolateral neck dissection, is the removal of the lymph nodes under the large muscle on the side of our neck, called the sternocleidomastoid, and are closely associated with the internal jugular vein and carotid artery. These lymph nodes should be removed only if there is biopsy-proven cancer in them. There are other important structures seen here that are not seen during thyroidectomy or a central neck dissection. These include the nerves to the lower lip (marginal mandibular nerve), ear lobe (greater auricular nerve), shoulder (spinal accessory nerve), tongue (hypoglossal nerve), voice box and throat muscles (vagus nerve, which later turns into the recurrent laryngeal nerve), diaphragm (phrenic nerve), and arm (brachial plexus). During a lateral neck dissection, all of these nerves should be identified and saved. They should not be injured.

The decision on when to perform a central and/or lateral neck dissection depends on the cancer type and stage. Please see these respective sections on this website for more information.

A central neck dissection is the complete removal of the lymph nodes underneath the thyroid gland (levels 6 and 7). These are the lymph nodes that thyroid cancer first spreads to when it moves beyond the thyroid gland.

In differentiated thyroid cancers, a central neck dissection should be done when:

- There are abnormal lymph nodes in the central or lateral neck that on biopsy show differentiated thyroid cancer.

- The thyroid cancer is “high-risk”, meaning it is larger than 4 cm, has grown outsize the thyroid gland (called “extrathyroidal extension”) or invaded the surrounding tissues such as the muscle, swallowing tube (esophagus), windpipe (trachea), voicebox (larynx) or nerve to the voicebox (recurrent laryngeal nerve), or is an uncommon aggressive variant, such as tall cell, columnar cell, hobnail, insular, diffuse sclerosing, or Hurthle cell, to name a few.

- The information gained from the central neck dissection is needed before deciding on whether to give radioactive iodine (RAI) after surgery. For example, radioactive iodine is recommended if more than 5 lymph nodes in the central neck have differentiated thyroid cancer in them.

A lateral neck dissection, also known as a modified radical neck dissection, or an anterolateral neck dissection, is the removal of the lymph nodes under the large muscle on the side of our neck, called the sternocleidomastoid, and are closely associated with the internal jugular vein and carotid artery. These lymph nodes should be removed only if there is biopsy-proven cancer in them.

Parathyroid operations

In the majority of cases which ranged from 85 to 95%, a solitary gland is responsible for the cause of Hyperparathyroidism. Most of these cases are caused by parathyroid adenoma and are found in one of the four parathyroid glands. By knowing the location and the side of the lesion, minimally invasive parathyroid surgery can be performed.

Indications for surgery in an asymptomatic Hyperparathyroidism (2)

1. Younger than 50 with serum calcium greater than 1 mg/dL.

2. Urinary calcium excretion greater than 400 mg per 24 hours or 10mmol per day

3. Medical surveillance is not desirable or possible

4. Creatinine clearance is reduced by more than 30%

5. bone density in the areas of the spine, hip, or forearm that is greater than 2.5 standard deviations below the peak bone mass (T score-2.5)

6. Surgery requested by the patient

Pre-op Preparation

Localization

Localization studies are imaging studies that tell the surgeon where the adenoma is located. It assists in the approach in the minimally invasive parathyroid surgery. The localization tests are sestamibi scan, SPECT-Sestamibi single-photon emission computed tomography, CT scan, neck ultrasound, and MRI. Your surgeon will often use one of these tests to localize your parathyroid adenoma and discuss the findings with you.

Anesthesia and Medical Clearance

The surgeries are performed under general anesthesia. Patients with co-morbidities will require medical clearance from their medical service or internist before surgery.

Positioning

The patient is in a supine position with the neck hyperextended to ensure full exposure of the neck. The patient is adequately padded to avoid pressure ulcers.

Duration of the operation

The duration of the actual operation can range from 15 minutes to 120 minutes, with a median blood loss of 15 mL.(3). Because the parathyroid glands can have an ectopic location, surgery can often take time in locating the parathyroid adenoma.

Surgical risk of parathyroidectomy

Your surgeon will explain the procedure in detail, and patients are advised to ask questions and concerns before signing the informed consent. Patients are advised to write down their questions before seeing the parathyroid surgeon so they can be answered. The possible risk of parathyroidectomy is postoperative bleeding and hematoma, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, hypocalcemia, and hypoparathyroidism. The incidence of postoperative bleeding or hematoma is reported as 0.6%, while recurrent laryngeal nerve injury is reported at 1.1% (3). Hypocalcemia, which is manifested as finger paresthesia, peri-oral numbness, and muscle spasm, is transient. Permanent hypocalcemia was reported at 0.5% to 3.8% (3).

Parathyroidectomy

Because the parathyroid gland is intimately related in anatomical location to both the thyroid gland and the recurrent laryngeal nerve, it is our practice to perform the surgery under nerve monitoring to ensure and prevent nerve injury. A baseline intraoperative PTH is drawn before the surgery to serve as a baseline. Once the patient is under general anesthesia, the surgical team performs a timeout procedure to ensure the localization and side of the surgery. The operative site is then cleaned with an antiseptic solution followed by the placement of sterile drapes. The incision is placed in the neck crease line, and the incision is carried down several layers of the neck, namely, the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia, strap muscle, until the thyroid gland is visualized. The thyroid gland is then rotated, and the parathyroid gland is isolated using sharp and blunt dissection. Once the parathyroid adenoma is isolated and removed, and intraoperative PTH is drawn several minutes apart. Reduction of 50% of the intraoperative PTH is considered a cure. The operative site is closed in layers, and the skin is closed in a plastic surgery fashion.

Recovery after Parathyroidectomy

Activity- if the patient feels tired, the patient is advised to have enough sleep, which would help in the recovery. It is recommended that your head up be at least 30° to reduce the swelling in the operative site. The patient should avoid strenuous activities for the next two weeks. The patient is advised to walk daily to prevent blood clots in the leg.

Diet- if the patient is having pain during swallowing, the patient should take the recommended pain medication prescribed and start either a full liquid diet or a soft diet depending upon the tolerance of the patient.

Incision- most incisions are closed in a plastic surgery manner, and the skin is closed using skin glue or steri-strips. The patient can shower immediately after surgery since the skin glue is waterproof. Patients can use a cold compress to provide relief in the incision site pain. The skin glue in the incision site will begin to slough off within 2-3 weeks. The patient can either clean the area using either alcohol or soap and water.

Follow-up with your doctor after surgery- The patient is given instructions to follow up with your surgeon to check on your condition and incision site. You should also make an appointment with your internist for a medical follow-up. Your surgeon will discuss the pathology results. If you have any questions or concerns after surgery, you should contact your surgeon.

References

1. Khan M, Jose A, Sharma S. Physiology, Parathyroid Hormone. [Updated 2021 Sep 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499940/

2. Bilezikian JP, Khan AA, Potts JT., Third International Workshop on the Management of Asymptomatic Primary Hyperthyroidism. Guidelines for the management of asymptomatic primary Hyperparathyroidism: summary statement from the third international workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Feb;94(2):335-9.

3. Sadaf Batool , Osama Shakeel , Namra Urooj , et al. Management of parathyroid adenoma: An institutional review. J Pak Med Assoc.2019 Aug;69(8):1205-1208.